“I Never Saw You As A Mother”: Disability, Motherhood, and Personal Autonomy

by K. Bannerman

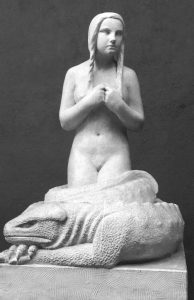

When Marc Quinn’s statue, Alison Lapper Pregnant, was revealed in Trafalgar Square in 2005, it sharply divided the art world. While the piece was originally inspired by the lack of positive representation of disability in public art, it was met with disgust by some critics, who described it as ‘like some 19th-century fairground exhibit’ and ‘rather ugly’. It’s a powerful piece, partially because it addresses disability, motherhood, and a woman’s right to control her future. Yet some critics seemed to ignore the fact that the subject is a real person, and reduced her positive portrayal into one of revulsion.

What does it say about the audience when they interpret an actual person – one who is firmly in control of her own representation – as ugly? Does it dig into the viewer’s personal insecurities, their fear of losing control? Does it frame motherhood as a prison, in which one has no agency or self-determination?

The trope of the disabled mother, which appears from time to time in the horror genre, plays upon those same insecurities. However, while it’s often played for shock value, it can also be subverted and challenged, depending upon the character’s ability to control their situation. Two examples illustrate this wide gulf between authority: the pregnant women revealed at the end of ‘Bone Tomahawk’, and the recently-pregnant matriarch in the episode ‘Home’ of the television show, ‘The X-Files’.

‘Bone Tomahawk’ follows a group of characters who are taken prisoner by inbred cannibals in the American West. Spoiler alert: the strongest and most masculine characters are killed, while the injured, the old, and the female characters triumph and survive. However, as the movie draws to its conclusion, the women of the cannibal tribe are revealed to be quadruple amputees, who hold no power over their existence and are used only for their reproductive qualities. All personal autonomy has been stripped away. They are seen as utterly without value by the survivors, and left behind.

In diametric opposition, Mrs. Peacock from ‘Home’ is in complete control of her situation. She is originally framed as a victim from the perspective of the main characters, and the audience is invited to be horrified by her situation. In fact, this was the only X-Files episode to get a viewer discretion warning, as censors felt it was too upsetting for the general public. However, the story soon revealed that she is in complete control. She is not a victim, for her boys have placed her at the top of their family unit, and she wields motherhood like a weapon, sometimes with murderous results. At the end of the episode, Mrs. Peacock is the one doing the leaving.

The use of disability or motherhood to provoke a negative reaction is not new in the horror genre, but using these subjects to symbolize victimhood subtracts from the reality of such an experience, where real people navigate their lives with intention, purpose, and strength. How we assign agency to the subject allows us to elevate the characters from helpless to powerful, from victim to victorious. It encourages an audience to see disability and pregnancy, not as frightening or imprisoning, but as a genuine expression of the human condition.

- When Fox Mulder turns to Dana Scully and admits, “I never saw you as a mother,” he seems to be commenting on her expression of compassion. However, seen through the lens of the episode, perhaps the comment can be interpreted as a nod to Dana’s ability for leadership, calculation, and sometimes ruthlessness.