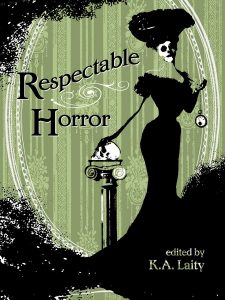

Respectable Horror

edited by K.A. Laity

cover by S.L. Johnson

‘Do serial killers, glistening viscera, oceans of gore and sadistic twists make you yawn behind a polite hand? Are you looking for something a little more interesting than a body count? These are tales that astonish and horrify, bring shivers and leave you breathless. You may be too terrified to find out what happens next – but you won’t be able to resist turning the page. We’ll make you keep the lights on. For a very long time.’

Contents:

Introduction by K. A. Kaity

The Estate of Edward Moorehouse by Ian Burdon

The Feet on the Roof by Anjana Basu

Spooky Girl by Maura McHugh

Recovery by H. V. Chao

The Holy Hour by C. A. Yates

Malefactor by Alan C. Moore

A Splash of Crimson by Catherine Lundoff

In These Rooms by Jonathan Oliver

A Framework by Richard Farren Barber

Running a Few Errands by Su Haddrell

Miss Metcalfe by Ivan Kershner

The Little Beast by Octavia Cade

The Well Wisher by Matthew Pegg

Where Daemons Don’t Tread by Suzanne J. Willis

Full Tote Gods by D. C. White

Those Who Can’t by Rosalind Mosis

The Astartic Arcanum by Carol Borden

Opening Paragraphs of Respectable Horror

Cousin Edward’s estate would have been a lot easier to settle had he the decency to leave his corpse behind, although I don’t suppose he had much choice in the matter.

Edward disappeared in the pellucid light of a warm summer’s day. There was no-one else: we were both only children and our respective parents are dead. Neither of us had girlfriends, or ‘partners’ as it seems we must now call them. I obtained power of attorney to manage his affairs.

In the end my only option was to have him declared as presumed dead. He left no will—who would at his age? Everything came to me by the rules of intestate succession. The estate was substantial, and very welcome: I was working to complete my doctoral thesis and flat broke, spending most of my time in the stacks of the university library or in the National Archives.

I found Edward’s journals when I first tidied his flat. His rooms surprised me by being full of framed family photographs. He had never seemed to be a family man, always buried in his research, but there we all were, the generations frozen and preserved behind glass. I even recognised some of them, and was pleased to see the redoubtable Great-Aunt Megan, whose regular grace at Sunday lunch—bless us and bind us, and hide us in a hole where the Devil can’t find us— rang clear in my memory, though she’s been dead for twenty years.