Project Runway

I used to watch American Chopper with my good friend alex. If you haven’t seen the show, it’s about a family owned and operated custom motorcycle shop. It became a huge media deal. You can’t stop in a New York State rest stop without finding a selection of Orange County Choppers shirts. Alex and I liked seeing the process involved in making bikes. We liked seeing people work together and solve problems. And when the show went batshit crazy with drama, we just stopped watching. I have rubbernecked as much as the next morally-compromised person, but it turns out that I am more interested in seeing the creative process than distressed or exhausted people acting out, let alone a family tear itself apart.

Early on in American Chopper, I noticed that bike designer Paulie Jr. kept building the same bike. He had no interest in building a bike that wasn’t one he liked. He complained about building an “uncool” Santa themed bike that would entertain kids in a local holiday parade. Though it’s possilble seeing how happy little kids could be made by the uncool caused his heart to grow two sizes that day because eve after building a few of his dream bikes, he started designing ones that took his clients’ desires and taste into account. And I was fascinated by Paulie Jr.’s evolution because some artists never get past building the same bike over and over. We can all plateau. After being driven away by the too painful interfamily drama of American Chopper, I picked up on Project Runway and I got some of the same satisfaction out of it that I did with American Chopper. Every week, Project Runway reminds artists that you have to figure out how to do something your way and you have to know when to drop something that’s not working.

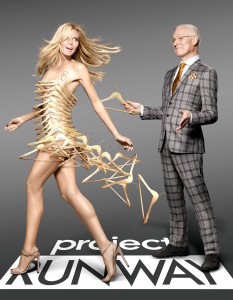

On Project Runway, designers compete to show a collection at New York Fashion Week as well as win prizes that vary every year, but always include: a chunk of cash, make-up services from companies ranging from L’Oreal to Mary Kay and a sewing and embroidery studio. Model Heidi Klum gives the designers a challenge and then they have one or two days (most often one, lately) to create their design. The challenges include designing around a theme, making avante-garde clothes, creating their own fabric designs, or working with “unconventional materials.” The latter challenge is often the most fun, as designers work with materials they’ve gotten at the grocery store, a flower market, ripped from a car, or found at Coney Island, for example. The designs are judged by Heidi Klum, Marie Claire fashion director Nina García, and, in the early seasons, designer Michael Kors or, in more recent seasons, designer and cartoon tom cat Zac Posen. There’s also a weekly guest judge who might be another designer like Betsey Johnson, a costume designer like Bob Mackie, a tv star, a fashion blogger or an executive from whatever corporation sponsors the challenge. Each week, one designer wins and one designer is eliminated or “auf’d,” after Klum’s habit of saying “Auf Wiedersehen” to losing contestants.

Sure, there is ginned-up reality show drama, weird product placement (why keep that refrigerator in the shot?) and heavy-handed corporate sponsorship, but I watch for the process of creation, the struggle to make something within insane parameters and for Tim Gunn. Gunn is the designers’ mentor. As Parson’s New School of Design former chair of fashion, he is a man who understands himself as an educator first–which also leads to some charmingly awkward voice-overs and readings of scripted product placement.

I mention Parson’s, Marie Claire and corporate sponsors to give a sense of the variety of perspectives and some of the competing tensions in the show. Marketing and art. Experts and people who just like what they like. People who really know what they are talking about and, sometimes, people who really, really don’t. And these tensions encompass the tensions in fashion—and other commercial art pretty well. Sometimes it means gorgeous couture gowns and sometimes that means a tortured attempt to make a Samsung tv relevant in a sponsored challenge as Tim gunn awkwardly stands by a television reciting: “Your new challenge is intended to test your ability to push the boundaries of design, just as Samsung has done here with their new ultra-high-definition TV.”

But even during the most convoluted challenge, I still enjoy watching the designers decide what to create and how. Lessons I’ve learned the hard way are well-illustrated by the show and pithily summarized by Tim Gunn. “Make it work” is much more concise than what I generally think of as “working with what you have,” or “work with yourself or around yourself.” It might be a catchphrase now, but “make it work” summarizes a lot about creation.

In Project Runway‘s work room, I see designers struggle every week with knowing: when to abandon the ideal in favor of making something as good as it can be now; the difference between tenaciously trusting yourself and stubbornly refusing to see the fugly or sometimes far too revealing truth before you; knowing when to jettison something that’s not working, even when you love it; learning that constraints of time, materials, budget can be liberating. In any kind of creative project, it’s easy to get hung up on what something should be, blinding you to the difference between what you are trying to make and what you have made, and preventing you from following your creation to its best conclusion.

I hear the designers say things that I have thought or said about my own writing. It’s hard to recognize that what you want to accomplish and what you have accomplished are not necessarily the same. And clinging too strongly to either can ruin your work. I’m doing better with that, but I would like to be able to communicate more effectively to a variety of people when they ask for an opinion or an edit. Tim Gunn demonstrates an approach to art that, if not universal, is easily adapted, and there’s a lot to learn from how he talks to individuals to help them achieve their best work. Being able to say the right thing in a way that cuts through mental static, uncertainty, distress, even absolute certainty to help someone see what they have done and what it can be is tremendously difficult. I admire Tim Gunn’s ability to calibrate his responses and suggestions so that they are honest, clear and effective with each individual designer. He finds a way to communicate his concerns effectively to a variety of people about a variety of designs. And he’s so good at it that it’s more noticeable when he can’t find a way to help a designer because he almost always does.

On Project Runway, you can recognize the designers in trouble by the things they say. Almost anyone who says, “I’m going to stay true to my vision” is doomed. There are designers who have trapped themselves during a challenge because they can only imagine bad clothes that they don’t like. They usually say, “I don’t do red carpet gowns” or “I don’t do color.” The designers who confuse design with good sewing skills remind of me of people who think good writing is mostly excellent spelling. And there are the extremely talented but defensive designers who have a hard time listening because they’ve always been the best in the room—or because they’ve been alone with their work for too long. Sometimes these same designers crumble after receiving criticism, losing faith in themselves. The more experienced designers either scrap the design and start over or try to make what they have work. And if they really do know their own vision, and their own strengths and weaknesses, they might decide to stay with their original design. And they might even win. The trick, as always, is knowing how to make it work.