Reading to Save Your Soul

Alex Bean

A few nights ago I noticed a recent shift in my reading habits. In a post on Facebook I mused that since the US Presidential election in November I had begun reading a lot more fiction than usual. My habit generally being rather massive works of non-fiction and history, this seemed notable. In the comments on my Facebook post a friend, himself a writer, told me to keep it up. “Read all the fictions. Fiction will save your soul, if not your life.”

That idea has really struck a chord with me, especially in a domestic political climate mired in the toxic racism and incompetent xenophobia of a populist demagogue. To that end, much of the fiction I’ve been consuming at a faster-than-usual pace has incidentally turned out to be the perfect antidote to the uninformed hatred and suspicion permeating from the White House.

In November, right after the election, I felt completely unmoored. My whole sense of the foundations that underlie my society felt undone. So I went all the way back to the source and re-read Gilgamesh. It’s always sort of awesome (in the Old Testament sense of the word) to go back and read texts from the very origins of human civilization. Glimpsing the formal and dramatic power of literature already being harnessed so far back in the fog of time is intimidating and impressive. I also couldn’t help but be amused that the city vs. country divide made so stark in the election can just as easily be found in the wrestling match between Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

As I finished the work, one particular passage stuck out and seems especially relevant in the pursuit of saving my soul via fiction.

“What you seek you shall never find.

For when the Gods made man,

They kept immortality to themselves.

Fill your belly.

Day and night make merry.

Let Days be full of joy.

Love the child who holds your hand.

Let your wife delight in your embrace.

For these alone are the concerns of man.”

Those lines echoed through my mind as I reflected on two pieces of fiction by people being actively persecuted by the short-fingered vulgarian in the Oval Office. One of them is The Moor’s Account, a novel by Moroccan-American author Laila Lalami, which I first read a few years ago. The moor in question is Estevanico, a once-successful slave trader in Morocco who sells himself into slavery in Spain and eventually becomes the first recorded African to immigrate to the Americas. \

Seeing the arrogance and violence inherent to European colonization of the Americas from the eyes of a Muslim from Morocco fundamentally alters the whole American idea. It lets the reader re-imagine this country means by finding the stories in the gaps and ellipses of history. I’d like to imagine that reflection like that might be enough to save the soul of my country if enough people read it and took it to heart.

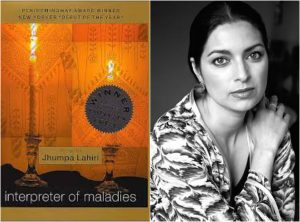

The other work of fiction, which I started the week that Trump signed his odious Muslim Ban, was Interpreter of Maladies by Jumpa Lahiri. The Pultizer-winning short story collection mostly focuses on Indian immigrants to the United States. What struck me, again and again, throughout the nine stories in the collection, is how Lahiri uses her understated prose to sketch out characters with thoughts, hopes, fears, and dreams that are at once universal and highly specific. As with Gilgamesh, a quote (or two) may best illustrate her effusive powers.

“While the astronauts, heroes forever, spent mere hours on the moon, I have remained in this new world for nearly thirty years. I know that my achievement is quite ordinary. I am not the only man to seek his fortune far from home, and certainly I am not the first. Still, there are times I am bewildered by each mile I have travelled, each meal I have eaten, each person I have known, each room in which I have slept. As ordinary as it all appears, there are times when it is beyond my imagination.”

“In those moments Mr. Kapasi used to believe that all was right with the world, that all struggles were rewarded, that all of life’s mistakes made sense in the end.”

We may be doomed to live in interesting times and I still find myself full of worry and outrage. But reading those lines made the whole sad, fearful displays which dominate the news shrink from my mind. Fiction, perhaps more than any other format, has the power to cut through the noise and make you look at yourself and the world in a new light. We’re all seekers like Gilgamesh and strangers in a strange land like Estevanico and ordinary people whose achievements are beyond imagination. No one man, no matter how foolish can steal that from us. That’s what will save our souls and that why I’m reading fiction right now.