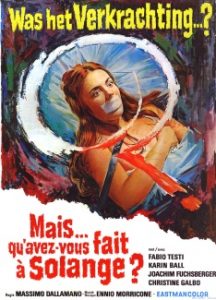

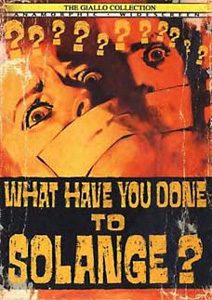

‘What Have You Done to Solange’ Exposes the Legacy of Misogyny

By Leslie Hatton

Horror films have long been derided for using women—and women’s bodies—as props to be sexualized, violated, and discarded, with both Italian horror and American slashers being singled out for their misogynist portrayals of women. Massimo Dallamano’s What Have You Done to Solange? represents a unique entry in the horror canon. Not only is it a tightly-plotted Giallo and an early slasher, it also upholds and subverts genre tropes and cultural expectations through its depiction of women. Even the title of this film seems different from the norm, seeming to question the morality of what was done to the titular character and the implied trauma that resulted from this mysterious and unnamed action.

Set in London, but using Italian dialogue, What Have You Done to Solange? chafes against the restraints of the typical Giallo by contrasting the conservatism of a Catholic girls’ high school with the sexually charged atmosphere of Italian cinema. Although the film is about a series of murders of young women, it is told through the plight of Enrico Rosseni, a young professor of phys ed and Italian at St. Mary’s school who is considered the “cool” teacher for being far less conservative than the rest of the cast.

Enrico is cool, all right. So cool that he’s cheating on his wife, Herta, with one of his students. Herta is portrayed as a vengeful shrew who clearly suspects him of infidelity but the film presents Enrico as the sympathetic character. When one of Enrico’s fellow teachers, Professor Bascombe, casually mentions that he suspects Enrico of having an affair with Elizabeth, Enrico confirms it. One would expect him to lose his job or be reprimanded, but Bascombe brushes it off, even suggesting that no one could blame him with a wife like Herta.

Still, Enrico is not the only man to exhibit despicable behavior in Solange. Professor Newton continually peeps through a hole in a glass window into the girls’ locker room, in a scene that is the literal manifestation of the male gaze. Also subject to the male gaze is the dead body of the first murder victim Hilda Erickson. Inspector Barth of New Scotland Yard passes around the gruesome crime scene photos to the staff at the school. In one of the more literal cinematic examples of misogyny, it turns out that Hilda has been stabbed in the vagina. It’s death by rape, with a large knife as the substitute for the penis.

For all its grisly detail, Solange is a gorgeous film. Prolific porn director Joe D’Amato lensed the film, and elevates what could have been a sordid exploitation film into something approaching high art. D’Amato uses extreme close-ups of women’s faces to convey an intimate understanding of the struggles that they are facing, or in one scene when Elizabeth and Enrico are making love, the pleasure that Elizabeth is experiencing. At other times massive wide-angle shots indicate the lack of power of the characters in the film, such as the imposing stairwell at St. Mary’s school, or the park in which Enrico and Herta are having a picnic.

When Elizabeth and Enrico are kissing in the boat along the banks of the Thames, the camera is voyeuristic but refined, with dappled sunlight and green foliage obscuring the two lovers’ bodies. This scene is also vital because it sets the entire narrative of the film into motion. Not only does Enrico become enraged at Elizabeth’s hesitancy to have sex, shouting “There’s always something that stops you from being a normal girl!” (using “normal” as code for “sexually active”), he also dismisses what he interprets as a contrived excuse: Elizabeth claims to have seen a murder take place, and as it turns out, it’s Hilda Erickson who is the victim. Instead of being sympathetic and tender, Enrico clearly feels like he’s owed something, and in typical macho fashion, denies the validity of what Elizabeth has witnessed, until the truth is revealed in the news. Rather than apologizing, he begs her not to tell the police, fearing for his reputation, not hers.

Elizabeth, however, has been damaged, and it’s impossible not to sympathize with her. She suffers from PTSD and continues to have flashbacks to the murder scene. Intriguingly, Dallamano uses this to give Elizabeth some autonomy. Both of her flashbacks take place in sexualized situations, which only exacerbates the feeling of sex as an act to which one must submit. Then she works up enough courage to let her voice be heard, coming forward to the staff at the school about what she has seen: it was a man dressed as a priest who killed Hilda.

Not all men in Solange are as despicable as Enrico. Shockingly, it’s Inspector Barth who calls Enrico out on his bad behavior. He calls Enrico into the police station for questioning, not as a murder suspect, but as someone who has something to hide. “You are thinking about something other than Hilda,” he accuses him, voicing something many watching the film are probably thinking, something which Elizabeth doesn’t have the freedom to say.

More students at the school are killed and so is a local woman, all in the same way as Hilda Erickson: a knife to the vagina. The teachers and staff members at St. Mary’s school are questioned, but despite the revelation that it may be a priest, none of the priests at the school are considered suspects. Only after Elizabeth is drowned in the bathtub is Enrico determined to find out the identity of the murderer. Is it his conscience making itself known or merely the desire to clear his name? We never really know. He and Herta, who for some reason decided to reconcile, start asking questions and eventually the truth is revealed. Her name is Solange.

Now we have a character in the film to attach to its title, as well as a face. Camille Keaton, the protagonist of the iconic rape/revenge slasher I Spit On Your Grave from 1978, is Solange. In this film she is unable to get revenge on those who destroyed her life. She was part of a clique with other girls at the school who had orgies with older college boys. After Solange got pregnant, her “friends” feared exposure and in a twist of internalized misogyny, convinced her to have an abortion. The experience was so traumatic that she has been rendered mute, and is suffering from “infantile regression.”

Here the film presents contradictory depictions of women. While the sexual agency of the young women can be seen as a good thing, Enrico is disgusted when he learns about it, suggesting that the girls are probably on drugs, too. The double standard is obvious: he can cheat on his wife with a student, but those same students shouldn’t be having sex of their own volition.

As it turns out, it’s Bascombe, Solange’s father, who has been killing everyone responsible for his daughter’s predicament, something which seems honorable until you consider the sexualized nature of the murders. In his shame and rage, he took on the role of vengeful vigilante. His daughter’s suffering is written all over her face at the end, but not even Herta offers her solace. Solange is presented as damaged and unclean, as if her trauma is infectious. Inspector Barth says it best in the film’s closing line, “Solange has been paying for everybody.”

Misogyny victimizes women in multiple ways: it characterizes female sexuality as bad while upholding male sexuality as good; it transforms us into chattel; and encourages us to harm our fellow sisters in order to be favored in men’s eyes. What Have You Done To Solange? reveals that the damage has come full circle. At a time when victims of misogyny are condemned, harassed, and disbelieved, we must ask the sobering question of not what was done to Solange, but why it had to happen in the first place.