Finding the Words

by Rue Karney

When editor Margret Helgadottir first asked me to contribute to the Pacific Monsters anthology I faced a dilemma. Margret asked for a monster that came from Australian history and culture. But as a non-Indigenous person living in a country steeped in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, I needed to invent a monster that reflected this country and its existing First Nations’ peoples while not stepping into cultural appropriation.

My first thought was to write about a mass murderer — a monstrous human. Margret gently vetoed that idea because it was outside the aims of the anthology. Nevertheless I wanted to come up with a way to portray the violent men who made it their mission to kill, maim and destroy in their quest to steal land from those who had cared for it for more than sixty thousand years. These men, and there were many of them, were the mass murderers I wanted to write about. My challenge was to take their actions and create a believable monster within a story that accurately reflected their deeds but also contributed towards a conversation around the truth of Australia’s frontier wars.

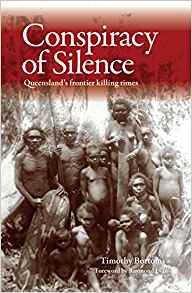

Australia’s First Nations peoples have never ceded this land. In the 150 or so years after Captain James Cook landed at Botany Bay, an event that started the colonisation of Australia, there were hundreds of battles as the white invaders drove the Indigenous peoples off their country. There are several excellent books on this part of Australia’s recent history but as I live in the state of Queensland I took Timothy Bottoms’ The Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland’s Frontier Killing Times as my guide.

In his book, Bottoms provides the statistic that, conservatively, the figure of Aboriginal peoples killed in Queensland in the frontier wars is around 48,000. These men, women and children were killed because they were fighting for their own land, land that the Europeans stole from them. Bottoms quotes multiple original sources that detail attacks that occurred across Queensland including shootings, poisonings, rape, bashings and other horrific violence. There are no words to describe the horror of these atrocities that led to this devastating figure. Yet, that was the goal I set myself as a fiction writer approaching the task of writing a story for Pacific Monsters: I had to find the words.

I had a conversation with a close friend, an Aboriginal woman who grew up in the far north of Queensland around Cape York, about a particularly brutal man who was responsible for several massacres. This man’s name brands the country up there. A major river is named after him, as is a national park. Streets are named after him. A hotel is named after him, and to this day there are First Nations’ peoples who refuse to set foot in it. My friend told me that, such was the horror of this man, there is a legend that when he died he was buried upside down to make sure he could never return and terrorise the land again.

Here was my monster. A violent man, guilty of mass murder, who returned from the dead but because he was buried upside down he could only walk on his hands. Thanks to Bottoms’ research, I had first-hand accounts of the type of atrocities my monster, and others like him, committed. My next challenge was to build the story around him. And for that I needed a name for my central character.

I can’t recall what name I used when I began my first rough drafts of the story but I do know that nothing came together until I settled on the name Providence Slaughter. Her name is intentionally literal because it marries the two key aspects of the story — death and wisdom. Providence is a woman ignorant of her own ancestry and so ignorant of her family’s involvement in this horrendous part of Australia’s history. In writing her story, I wanted to bring this history to light in a way that her character would not only accept its truth but also do something with the knowledge.

Providence must reconcile the truth of her past with her present situation. She is disconnected from the land, as many non-Indigenous Australians are, in part because of her inability to recognise and accept past wrongs. The monster in my story is her past and her present just as the frontier wars that took place in Australia are our nation’s past and our present.

This is probably the most political story I have written because, despite the overwhelming evidence, the truth of the frontier wars is something some Australians find too unpalatable to accept. Yet the ramifications of the actions taken by white invaders continue to echo in today’s political, cultural, economic and social landscape. Young Aboriginal men in Australia are more likely to end up in jail than in university. The life expectancy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women is around a decade lower than that of non-Indigenous Australians. First Nations peoples are six times more likely to suicide than non-Indigenous Australians. These statistics are the result of inter-generational trauma; trauma that cannot start to be healed until Australia owns its bloody recent history and starts to make amends.

My monster story is not going to make a dent in these horrifying facts. But it tells the truth of the frontier wars, and the more stories out there telling this truth, the closer Australian society will be able to shift towards acceptance.

Rue Karney https://www.facebook.com/RueKarney/