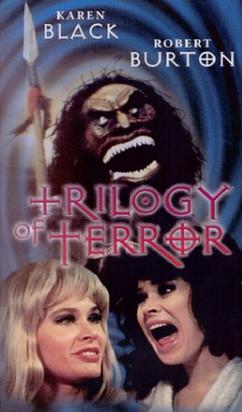

Once, Twice, Three Times a Villainess: Karen Black, Sex, and Twist Endings in Trilogy of Terror

by Angela Englert

Karen Black initially rejected Dan Curtis’ TV anthology Trilogy of Terror (1975), joining the production only after her then-husband, Robert Burton, was cast in one of the film’s sparse supporting roles. So she was the star, but she did it for her dude, which is appropriate given the movie’s ambivalence about women’s empowerment. Afterward, she may have had cause to regret it, as she believed that her performances in the film – because there were many – typed her as a horror actress. She was probably right, and she wouldn’t have been the first whose fearless brilliance in a genre movie closed doors rather than opened them. But she was fearless, and she was brilliant. Even if Trilogy were a proper theater-release film, her work would never have been acknowledged by the Academy, not in a movie where she gets chased for a third of it by a puppet, but no one will ever persuade me that Karen Black in Trilogy of Terror didn’t earn herself a statuette, even if it might have been shaped like a Zuni doll.

Trilogy was based on three Richard Matheson short stories, and they each bear the hallmarks of the spring-loaded twist endings and pulp horror he excelled in. If the punchlines seem a bit dated better than 40 years on, it’s at least partially because we’ve been audience to so much they have influenced in that time, from Fight Club to Puppet Master. The three vignettes featured in Trilogy center on three very different women, all played by Black, each taking the lead character’s name as the title of the piece. While there is no continuity among them, Trilogy ends up naturally being about all the ways a (white, heterosexual) woman in the 1970s could be victimized, not neglecting how she might best victimize herself.

The first story, “Julie,” is probably my favorite, and it’s still disquieting and quite fresh. Julie teaches at a college, and Chad (played by Black’s husband, and I’m not sure whether that makes this one more or less icky) is her student. We first meet Chad when he and a friend are sitting in the quad rating the attractiveness of the women around them. When Chad spies Julie, herself much more on the Velma than the Daphne side of things, he finds himself wondering what she looks like “under all those clothes.” It’s an idea he can’t shake, and so he pursues her with the unblinking predation of a Duran Duran song. When Julie yields to his advances, he takes her to a drive-in movie and drugs her soda. With Julie unconscious, Chad abducts her and at least takes pictures of her in sexually provocative poses. Later, he will use the pictures to blackmail Julie into a nonconsensual affair and – it is implied — pretty much any depraved thing Chad can imagine. The twist is revealed to Chad abruptly, as Julie suddenly refuses his commands during an assignation and declares herself bored. Julie explains, “Did you really think that dull, little mind of yours could possibly have conceived any of the rather dramatic experiences we’ve shared? Why do you think you suddenly had the overwhelming desire to see what I looked like under ‘all those clothes?’” It turns out that Julie has been psychically topping from the bottom, as it were, using Chad’s sadistic exploitation for her own jollies. And now that she’s bored, she has poisoned Chad’s drink – nice touch, Julie – before moving on to the next unwary victim, cloaked again in the habit of a plain, nebbish teacher.

I think what bothers me most about “Julie,” and Julie for that matter, is her monstrousness depends on how she relishes the feigned powerlessness that makes her a victim of abuse. Not a D/s relationship, but assault, coercion, loveless abuse. If she were only a black widow luring men, especially a wicked man like Chad, to their doom, that would be relatively unremarkable, and it’s not hard to understand a powerful person wanting to be dominated in a sexual relationship. That’s a cliché. But Julie wants to be victimized, and she puts down elaborate roots in a life where she has fashioned herself into an ideal victim. It’s not simply about destroying Chad’s soul, if he has one, and it’s not simply about lying in wait, laughing behind her hand at his presumption of her innocence, though she seems to enjoy that, too, in the end. Maybe if Black’s portrayal were less persuasive, Julie’s portrayal would be less persuasive, and it would be easier to write her off as a kinky monster whose inconsistency is in service of a plot that takes a hard right turn into a twist ending. But Black gives Julie too much interior life to believe that, and we see this in her public humiliation by Chad, her private displays of grief for her concerned roommate. That’s where the real creepiness, the insatiable wrongness in ”Julie” asserts itself. It speaks to twin destructive myths about women’s empowerment and enjoyment of sex that still lurk in our culture everywhere from pornography to romcoms: that women make themselves powerful only at the expense of men and that women fundamentally want to be – let’s say overpowered by men. And that’s disturbing as hell.

Black similarly played both sides of a very bad penny in “Millicent and Therese.” Of the three stories, this is one that probably has aged the least gracefully, only because the twist – surprise, sisters Millicent and Therese are one person with two personalities and a blonde wig – seems fairly hackneyed by now. But I have to say that Black’s portrayal of the two “sisters,” plain, obsessive Millicent and gorgeous, licentious Therese, is convincing enough that it’s still possible to doubt the plot you see circling for a landing is what’s going to happen until it’s over. I particularly admire her zeal as Millicent, who anticipates Donald Pleasance’s Dr. Loomis in Halloween with passionate harangues about Therese’s inborn evil, seducing their father and murdering their mother, and her own plans to stop her, once and for all. And Black’s self-satisfied malevolence as Therese is similarly unimpeachable.

The last part of Trilogy is the story that has made the biggest pop cultural impact, a one-woman play that has Black as Amelia, a woman torn between filial duty to a codependent mother and being an independent adult with a boyfriend. Amelia’s strained one-sided phone conversations with her mother and boyfriend are masterful work by Black, as she tries to juggle a standing dinner date with mom and a birthday dinner with her boyfriend. There’s so much emotional weight shifted in these scenes, particularly as Amelia finds herself rationalizing her mother’s demands to her boyfriend, abruptly starting a fight with him. Her loved ones alienated, Amelia’s night takes a bizarre turn for the worse as she’s chased around her apartment by her would-be gift to her anthropologist boyfriend, a surprisingly resourceful, possessed Zuni warrior fetish doll. The whole thing might have been silly, but Black sells it all, making her struggle with the toyetic, fanged symbol of her thwarted independence immediate and visceral. After jamming the doll into a blistering oven, Black’s jagged smile reveals a final character in the story’s twist ending. Amelia has destroyed the doll, but becomes possessed by the Zuni warrior inside, who now waits to cut mother’s apron strings along with mother’s everything else.

There was no reason particularly Dan Curtis needed to cast one actress to star in each of the vignettes, but it was a wise choice, not only because Black’s consistently excellent, but her presence also draws attention to the reverberating themes of women turning on themselves. Not only is she every heroine, but she is also every villainess. It’s all in her. Without an actress of Black’s skill, it’s doubtful how well any individual story would have worked. They each require so much of their lead, not only to be plausible and pitiable, but fierce, physical, forbidding, and she largely has to do it all on her own. It’s a rare accomplishment that rightly has given Black a share of immortality and has given women still today a mirror of themselves in the eyes of a society that doesn’t know whether an unfettered woman is friend or foe.