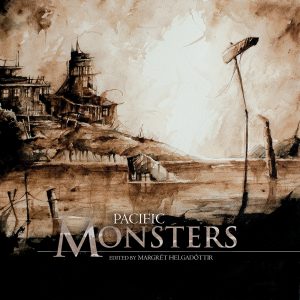

The FS Books of Monsters are a Horror series curated by Margrét Helgadóttir (and in the early volumes, Jo Thomas), who are women in horror.

MONSTER

Tina Makereti

It came out of the sea on a Saturday morning, heaving its body onto the rocks beside the boat sheds in the darkness before dawn. It sat in a shallow pool potted with black mussels and a slick of seaweed while it took a few breaths, then drew itself up the stairs. It could smell rust and exhaust fumes.

The dragon boaters had woken it the day before, crowds of them, their barrage of noise muted only slightly by the shallow watery cradle of the harbour. Somehow the tides had brought it in as it slept, released from its bed in the depths of the Pacific by the rumblings of a quake. It wasn’t just their yells that woke it, or the slice of their paddles in the water—a thousand small splashes that sounded like storm rain from where it lay. They brought something else with their bright-painted hulls and racing arms. It felt them moving above, pushing against the limits of their age just as they pushed through the water, a hard-held breath waiting for life to happen. It felt the enormity of future somethings beating in their chests. It opened an eye and saw the firm thighs flash, the twist of wrist tendon.

It wanted them.

It watched all day, one eye and then two, from just below the surface. A girl looked right into one of those round dark lenses just before she plunged her paddle, but quickly dismissed what she had seen as reflection—the heat and sweat of the day causing distortion in her vision. Even so, that afternoon she developed an aversion to water, preferring to keep fingers and toes above. The others on her team teased when they noticed her reserve, dipping their own fingers in to splash her. The thing beneath could almost taste the juice in their taunts. It dreamed of nibbling their sweet digits.

Still, it stayed—calm, quiet, breathing in salt-wet infused pockets of air, readying itself for the closing of gills and opening of lungs. It could wait. The upper world would still be there when it was ready. Last time, the land under the sea had rumbled the thing up from below in great surges, wave after wave, until it found itself pushed up into the harbour and past, washing through a beachfront house with the massive tide. The house had been quickly abandoned when the sea came knocking; so it stayed awhile, slumping and sloshing from room to room, curious about the upper world. The house was wood, and spare, and the contents were now damp and sandy and preparing to rot. There it found a woman’s petticoat among some items pushed into a wet corner, and a framed family portrait that had remained miraculously nailed to a wall. It wondered about the smooth-skinned creatures in the picture, with their coverings and ruffles and silky heads. It reached thick fingers to the bulbed seaweed and baby mussels that formed stringy colonies on its own head, felt its own calloused black barnacle skin, and made a sound very like laughter.