A question on nationality

by Shawn Basey

It is an odd trend to only see regression in today’s world. We look at the last 18 centuries as a reversal of some sort, as though the pagan era were an idyllic time of matriarchy and peace, when neither were remotely true. Perhaps triggering this mindset was Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael, but here he’s referring to a time even before that, a pre-agricultural revolution time. But always this looking back to a mythical yesteryear, of better times – it is persistent throughout modern Western culture, whether looking only a few years back or millennia. This looking back is a political tool, of course, to inspire revanchism, to pass the blame game around and build up an active base of support. It is part of saying it’s their fault when the fault is not in everyone else, but in ourselves.

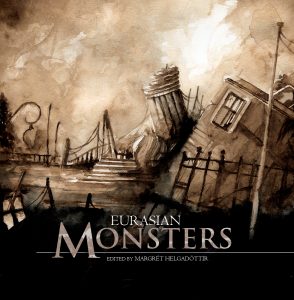

It is a point I bring up in my latest short story for the Fox Spirit Eurasian Monsters anthology, “Lysa Hora”, which takes place in Tbilisi, Georgia, my home. In Georgia, currently, they have long been undergoing a process of national identification. Ever since the latest unification of the country – the liberating of each half from the Ottoman and Persian yokes – there has been an ongoing struggle of the definition of “Georgian”. So much so, that the most respected writer of the time, Ilya Chavchavadze, concerned himself with the question of “Georgianness” throughout his years. The question was delayed by the Russian and Soviet occupations, only to be reignited after the fall of the latter.

It seems a settled question now: Georgian Language, Georgian Orthodoxy, and Georgian citizenship. But in a historically multicultural society – and one that remains so to a large extent – these are flailing definitions at best. Among native Georgian speakers, we find Orthodox and Catholic Christians (among others), Jews, and Muslims. There are four distinct languages within the Kartvelian (Georgian) language family, and one of those exists only outside of Georgia’s borders in Turkey. Among Georgian citizens and those who have lived here for centuries, we find not just Georgians, but Azeris, Armenians, Os, Abkhaz, Russians, and so on – a larger percent of minorities than all the other countries in the Caucasus region combined. Finally, there’s an ever-growing Georgian diaspora, many of whom have broken many of their ties with Georgia fearing it’s not civilized, wealthy, or modern enough for them.

Be that as it may, Orthodox Christianity is what many latched onto as the defining agency of “Georgianness” after the fall of the Soviet Union. And now many are looking towards Europe and identifying it with some brand of secular, even atheism, which casts a growing doubt in their Church. This sentiment, not shared throughout the population, is creating a growing unease about their role with the European West.

And though I don’t disagree with the direction they are looking, I do disagree that the Church – and the Christian Churches of Western Europe – are necessarily the catalysts of all that is evil in history. In fact, it is this viewpoint that is being driven by many in Europe and here, that’s being picked up and waved about as a sword by Russian propagandists. But let’s not go further with that. Let’s go further on why I don’t think Christianity was such a bad influence. Namely in regards to one single story: the Georgian creation myth.

Not much is known about the religion before Christianity. We know some of the primary figures of the pantheon, we know that both Zoroastrianism and the Greek pantheon were big here, and some of the larger myths, and that it has many influences from the Hittites. Most of the myths we know, like those of Amirani and others, have passed along into Christian stories, with the tales of Christian saints often having been transferred from pagan deities before them. The pagan myths held the strongest in the mountain regions, which were the last to Christianize and to this day still hold a great slew of pagan beliefs and practices, from mass sheep sacrifices to a loosely Christianized shrine practice.

In the ancient days, the world was split up into three planes: Zeskneli, Shuaskneli, and Kveskneli. Zeskneli being the home of the gods and the upper plane, Shuaskneli being our plane, and Kveskneli the home of demonic creatures. Shuaskneli is in mythology more of the battlefield between the two planes.

It is from the mountain people, the Khevsurs, that we get what is left of the story of Morige Ghmerti, the chief god, and his sister. Morige Ghmerti so hated his sister that he banished her from Zeskneli, and she was bent on revenge ever since. For every good creation he made, she made an equal, opposite evil creation. He made gods, she made demons; he made men, she made women. Inhabiting as they all did Shuaskneli at that time, it’s said that the gods finally got tired of battling the demons and left for Zeskneli, leaving behind men. Demigods persisted in banishing the demons from Shuaskneli, leaving behind women.

The situation being, all the bad in the world remaining was from women. The beings of Morige Ghmerti were civilized, social, divine. Those of his sister: wild, chaotic, demonic.

It is perhaps the only religious system in the world that has such a bizarre differentiation between men and women. We do get ideas of the subservience of women to men from other cornerse, but never the idea that women are inferior in such an absolute moral sense from the moment of Creation itself.

We have now in fashion this kind of pagan revivalism, which is made ironic in that it’s coming from the left. In the 19th century Europe, we had such a neo-folk movement, but that from the right, molding into the pseudo-mythology of the Nazi elite. Indeed, the right wing volkists still hold such beliefs today. You can find White Nationalists sprinkled all throughout the folk metal and other folklore communities. You find a rise of pagan symbolism as well, with the Slavic sun wheel, Nordic runes, Georgian Borjgali, and others being coopted by nativist/volkist groups.

The interesting trend in Georgia though – and indeed in many circles throughout the collapsed Soviet Union – is that instead of the neo-pagan revival, we see a neo-Christian revival. Looking back to a Christian utopia that never was.

What I’ve attempted to do in “Lysa Hora” is to turn these ideas around. We have the main character, Otar, a simple-minded taxi driver who is drawn in by the poisonous narrative “Georgia for Georgians”. He’s a hard-core Orthodox believer because that is the definition of Georgia that’s given to him. He rejects all things Western, and sees only the “gayropa” that’s being sold down the propaganda mills. Then there’s his sister, Tinatin, who he assumes is “perverted” by her Westernism. But actually, all that he sees in her as evil is innately Georgian, and the actual old Georgian mythos, with its heart devouring kudiani, is much more horrific than the liberal West. Indeed, Christianity itself is an alien religion, brought from the outside.

But it also echoes that question of national identity. “What is Georgian?” Is it Orthodox Christianity? Is it the paganism before it? Is it something current, something new? And I think we can replace this question of national identity with any nationality, not just Georgian. This period of globalization is a huge stress on identities. National, individual, and so on. It is of course, too hard to cast all those off and be the “New Human”, or a “globalist”. We as humans, need positive definitions by others, so we fall back into these accepted classifications. We find safety and reassurance, and that’s what we really need in this changing world.

***

Shawn Basey is originally from Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, and he first came to Georgia in 2009 as a volunteer with the Peace Corps. It was then he fell in love with the country and decided to stay. He is now married and has a son named after the founder of Tbilisi, the city which they call home. He works freelance as a writer, teacher, and editor and enjoys traveling the world with his half-Georgian family. He keeps up a regular blog at www.saintfacetious.com and has published the novel How It Ends and the short story collection Hunger, both available on Amazon. He’s currently working on a novel about Georgia during World War II with strong Georgian, Azeri, and Kazakh folklore elements.