A Caribbean Bloodsucker

Pedro Cabiya

It all started in the seventies. At least, it all started being reported then. A special decade that one. It’s a miracle the news got any notice at all. At the time, only one kind of news lorded it over all the others: UFO sightings.

Puerto Ricans were seeing strange lights moving in the sky with non-ballistic behavior everywhere, but most especially near the town of Lares and all along the number 2 highway in the south coast. Also in El Yunque, the famous, numinous forest reserve in the northeast. It became something to do during the weekends: entire families would drive to places of past sightings, get out of their cars and gawk at the skies. Some of them got lucky. Most didn’t.

At first, the idea seemed too simple to be disturbing or even credible. Too banal. Some cows had been found dead, not a drop of blood in them, and no wounds or marks of any kind. Then chickens. Then sheep, goats… It was high time it got a name, and someone obliged: El vampiro de Moca, Moca’s Vampire, because it was in the western town of Moca that the mysterious bloodsucker hunted its prey.

The seventies died, the eighties’ joie de vivre came and went, and then the nineties arrived with their grungy nihilism. And with them the old bloodsucker, after a 20 year hiatus.

It made its reappearance in the northeastern town of Canóvanas, a town near the skirts of El Yunque. It got rechristened by political satirist and TV personality Silverio Pérez as El Chupacabras (Goatsucker), effectively robbed of the sinister persona its original name had granted it.

Farce followed tragedy diligently when this second time around the mayor of Canóvanas, José “Chemo” Soto took matters in his own hands and scoured the countryside of his municipality dressed in camouflage with a posse of heavily armed vigilantes. They carried around a classic zookeeper’s cage where they planned to trap the creature. It returned to base empty.

This second time around the creature hit other countries too, namely Mexico. While our plight had remained invisible to the rest of the world, Mexico’s injuries, backed by a multimillion dollar media machine, spread widely and quickly. And all of a sudden, the Chupacabras, a quintessential Puerto Rican monster, became Mexican.

Puerto Ricans didn’t take this lying down. Having the Chupacabras stolen from under our very noses hurt more than whatever the Chupacabras could have done to our livestock. News articles in the press and TV defended the Puerto Rican roots of the monster. Panels discussed the issue. Mexican and Puerto Rican specialists debated heatedly in conferences and roundtables. The colonial status of our island (occupied by the United States since 1898) makes Puerto Ricans very sensitive to cultural slights and feisty when it comes to protecting the symbols of Puerto Rican identity. As a result, the Chupacabras entered pop culture and was transformed into a mainstream staple as recognizable and profitable as the zombie, also a Caribbean invention. Curiously, both creatures are featured prominently in Red Dead Redemption: Undead Nightmare, a horror version of the popular western themed video game.

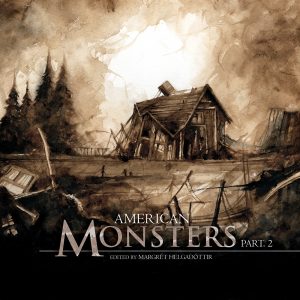

Though no one has ever laid eyes on the Chupacabras (the monster is known solely by the grisly victims it leaves behind), visual representations of it are more or less in accord: a small, thin, hairless dog-like wraith with a mouth full of teeth. The incoherence was never addressed: why does the monster have fangs, if it never uses them? The Chupacabras is a bloodsucker, yes, but a strange one in that it doesn’t bite its victims, whose bodies are sucked dry and yet remain unmarked. The story I’ve contributed to American Monsters Part 2, “Lay of the Land, Law of the Land,” finally resolves the mystery.