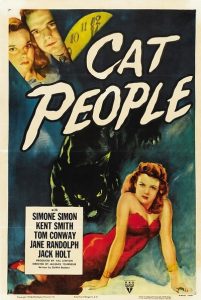

Cat People (1942)

Carol Borden

Cat People (1942) is a fine entry into the tradition of films that cause modernity—and gaslighting—some trouble by having a woman turn into an actual panther. Well, not as much a tradition as I might like, but it’s a start. Based on, Val Lewton’s short story “The Bagheet,” and adapted for the screen by DeWitt Bodeen, Cat People was produced by Lewton, directed by Jacques Tourneur and shot by RKO noir superstar cinematographer Nicholas Musaraca during the war at an extremely low-budget. There is no gore or on-screen transformation effects. There are only the shadows, a woman’s fear of herself and her own sexuality.

Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon) is an illustrator whose work is published in fashion magazines, highlighting the most modern of clothes. She is from Serbia, perhaps a refugee fleeing the Nazis and the war in Europe. She is definitely fleeing her home town, a village she and her fellow townsfolk believe was settled by devil worshippers who escaped execution in the 16th Century. And Irena is definitely trying to escape her fear that there is something evil inside her. Big cats fascinate Irena and her favorite subject is a black leopard at the Central Park Zoo. It’s an animal that an old maintenance man considers a killer. One day, Oliver Reed (no relation) approaches Irena as she draws. She tells Oliver (Kent Smith) she is fascinated by the big cats. And really, who wouldn’t be?

As they become closer, Irena tells him the story of her town. They were devil worshippers and were executed by the Serbian King John, aka, Jovan Nenad (1492-1527). The worst, however, escaped into the mountains. Now their female descendants are cursed to become panthers when they are sexually aroused or jealous. Oliver isn’t put off by her story. He is a modern lad and believes superstitious worries can be defeated by rationality and the love of a good man. Almost convinced that she was letting a fairy tale frighten her off of love, Irena accepts when Oliver proposes.

But when at a Serbian restaurant with Oliver and her friends right after the wedding, Irena is spooked when a cat-like woman approaches their table and calls her, “My sister.” Irena knows in her heart that this woman is one of her kind, another cat person. At home, Oliver has been respecting Irena’s boundaries, sleeping in another room and not pushing her to be intimate, but Irena becomes so distressed that he confides in his co-worker and best friend, Alice (Jane Rudolph). Alice suggests a psychiatrist, Dr. Louis Judd (Tom Conway). Unfortunately for everyone, Dr. Judd is a terrible psychiatrist. Dr. Judd falls in love, or in lust, with Irena.

Cat People was made in a psychoanalytic time, a time with a lot of optimism about modernity and science. Dr. Judd reflects it, cynicism and all. He doesn’t just pursue a scientific understanding of the human mind, but believes he already rationally understands what is before him and that he already knows all there is to know. More tragically, Judd believes knowing something is enough to cure or protect one. To Judd, Irena is just another another woman with a sexual dysfunction that is coded as “frigidity” or Lesbianism (“My sister”), albeit with an interesting clinical lycanthropic twist. Less philosophically, Judd is convinced that there’s nothing wrong with Irena that a more modern attitude in general and a healthy attitude toward heterosexual sex in particular can’t fix. Failing that, there is nothing wrong with Irena that sexual intercourse with a man, regardless of her fear or lack of desire, won’t fix. It is an era when what was considered sexual dysfunction sometimes called for realigning a woman’s sexual attachments with what we now consider “corrective rape.” (If I ever had a “corrective rape film festival” it would feature a lot of movies starring Sean Connery). Oliver was ahead of the curve compared to Judd at a time when it was not conceivable that a woman could be raped by her husband, especially when he is trying to help cure her fear that she could turn into a panther and kill him when she really gets going.

In saying all this, it’s not that I think Cat People is anti-rational. It’s more that it respects that while we pursue reason and understanding, we remember that are not already, inherently reasonable, rational, or objective. It leaves space for the unknown and the unexpected—the thing that is unbelievable but nonetheless true. It’s easy to think we already know everything and being modern has led us to believe so for the just over a hundred years or so that we have considered ourselves living in the modern world. While we might believe humans can know or understand anything, there is still a lot to discover, learn and understand. I believe Dr. Judd wants to help Irena. I believe he believes that once she has sex with a man, she will realize her fears are irrational and will fade away. But Judd makes a mistake in believing that he is only concerned with Irena’s well-being. Judd is too attracted and attached to Irena to be dispassionately, rationally helping her. He won’t listen to Irena. He already knows. And already knowing the answer is not scientific, my dear doctor.

But however you feel about his methods, Dr. Judd makes for some great cinema. He hypnotizes Irena, allowing for a fantastic, phantasmagoric dream sequence. Afterwards, Judd tells Irena that he can help her and recommends Irena tell Oliver nothing about her fears. Irena, however, doesn’t believe Judd understands or can help her. Irena comes home to find Oliver and Alice together. Worse, Irena find out that Alice knows about her problems. Irena is angry, embarrassed and appalled that Oliver would discuss something so private with Alice.

Alice is the first person to decide that Irena is not just haunted by superstitious fears, but is, in fact, transforming into a panther. Oliver turns to Alice for comfort and support. Alice admits that she loves him but would never do anything to threaten his marriage saying, “I’m the new kind of other woman.” Irena already knows Alice loves Oliver, though. And she becomes increasingly hurt and jealous. This leads to one of the most eerie stalkings of cinematic history. As Alice walks down the street, she thinks she hears a growling panther in the shadows. And at the YWCA, a panther (Dynamite) growls from the shadows and tears Alice’s bathrobe to shreds as Alice, terrified and vulnerable, treads water in the center Y pool. Irena then appears to ask Alice if she’s seen Oliver. Alice’s decision to believe Irena seems less a product of “feminine intuition” and more a decision to trust her instincts and not to deny her experience. Something happened at the Y. Alice doesn’t know how it happened, but she’s not going to pretend it didn’t. That’s how you end up dead.

After Oliver decides to divorce Irena and marry Alice, Irena menaces them both at their work. Oliver and Alice are now pretty sure Irena is a cat person. Dr. Judd, however, is still convinced he can fix Irena. He decides that what Irena needs is the love of a good man or at least the love of a terrible pschiatrist and he makes moves on her in her own apartment. Irena rebuffs him, but he continues and she finally transforms into a panther and slashes him. Because he is the kind of mental health professional who carries a sword cane, Judd draws a sword from his cane and stabs her. Wounded, Irena runs back to the zoo and opens the cage to the black leopard letting it kill her.

There is some crossover with another Val Lewton film, The Seventh Victim (1943). Both films share themes of Satanism, suicide and men who fall for troubled women. And both share two actors and at least one character: Dr. Judd. It is in The Seventh Victim that Dr. Judd’s terribleness as a psychiatrist is underscored. I mean, what therapist would be prepared for a woman who actually does turn into a panther? In The Seventh Victim, we discover that Judd has a reputation for sleeping with his patients—and perhaps worse. There is also a character played by the same actress who played the Serbian cat woman in Cat People, Elizabeth Russell. In The Seventh Victim, Russell plays Jacqueline’s neighbor Mimi. Mimi is terminally ill and decides to go out and enjoy herself one final time before she dies. Dressed up for her last fling, Mimi looks a great deal like the woman who calls Irena “sister” in Cat People. Is Mimi the same woman? Do Cat People and The Seventh Victim occur simultaneously? Is Dr. Judd that unlucky a psychiatrist? (And will there ever be a Dr. Judd, Occult Psychiatrist series?)

The sequel, The Curse of the Cat People (1944), is another Val Lewton production, this time directed by Gunther von Fritsch and Robert Wise and with another screenplay by DeWitt Bodeen. As with Cat People (1983) it is less satisfying to me than the original. It unfortunately completely lacks all cat people and suffers in some ways from its title. It does bring back the original cast as Oliver and Ann’s daughter Amy becomes friends with Irena, who might be a ghost but even I admit is probably not. Irena helps Amy through a difficult time—including a woman who tries to kill her, played, again by Elizabeth Russell. Curse of the Cat People is a thoughtful and melancholy film—and a bit disorienting to watch with Cat People. But again, there are no cat people. Even Irena appears only as a maternal and protective human albeit ghostly figure. And cat people are what I am here for.

Cat People was remade in 1982 starring Nastassja Kinski as Irena Gallier and Malcolm MacDowell as her brother, Paul. And director Paul Schrader unleashes all the power of 1980s color and style. Giorgio Moroder and David Bowie even provide the soundtrack. But in trying to make Irena’s secret more shocking–that she can only sleep with her own kind, i.e., her brother, it loses some of the power of the original. And it sadly adds rape back into the mix—this time making Oliver the rapist, which is just sad. It’s not like we are much more comfortable with women’s sexuality in 1982 or even 2018 than in 1942, no matter how much we would really like to be there.

One Reply to “Women in Horror : Cat People”

Comments are closed.