My Identity

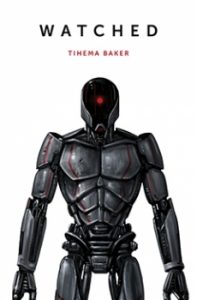

by Tihema Baker

Ko Tainui te waka

Ko Tararua te maunga

Ko Ōtaki te awa

Ko Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga, ko Te Āti Awa ki Whakarongotai, ko Ngāti Toa Rangatira ngā iwi

Ko Tihema Baker tōku ingoa.

This is my pepeha – my identity. It includes the vessel that brought my ancestors to Aotearoa New Zealand, to the mountains and river that geographically ground me, and the nations I belong to. For the Māori peoples of Aotearoa, identity is inextricably tied to whakapapa (genealogy), which demonstrates our worldview: we are the sum of everything that came before. It’s a profound recognition of the past and understanding of how it shapes the future. Everything that transpired, everything that aligned, everything that fell into place and resulted in our existence defines us. From the emergence of raw potential from the void, right up to the mothers who gave birth to us. By stating my pepeha, I am introducing myself as definitively as I can as Māori.

If you were to meet me face-to-face, however, it’s unlikely you would think I’m Māori. To most, I look white, or what we would call Pākehā; my skin is the freckly type that burns within a few minutes of summer sun, my hair is fair, my eyes are blue. Undoubtedly, if you met me on the street, you would assume I was white.

It’s a symptom of the world we live in, which insists on defining people by their skin colour or physical attributes. This directly contradicts that Māori worldview that identity has absolutely nothing to do with skin colour. I am the sum of everything that came before me. And if that means I am Māori, then I am Māori. There is no other qualifier.

That worldview doesn’t sit so well in a western, colonised society built on the exact premise that people are defined by their skin colour. Sure, today in New Zealand we don’t have laws that directly prejudice brown-skinned Māori (for the most part), and we don’t have overt displays of white supremacy (for the most part). But the remnants of a society built on racial profiling still infect our lives.

Like so many Māori children, I suffered through an education where teachers mangled my Māori name in almost every way imaginable. As an adult, I suffer through the same in professional environments, often having to correct colleagues on something as simple as calling me what I wish to be called. But there’s a unique element to this that comes exclusively with being a “white Māori”; having to justify being Māori to everyone else.

My mum recalls taking me as a toddler to the doctor, where the receptionist asked why she hadn’t given me a “nice” name like “Reuben”. Just a few weeks ago I caught an elevator with a woman who works at the same place I do and she asked, “How come you have a Māori name?” When I told her what I thought would have been the obvious answer – that I am Māori – she responded, “But you have red hair,” like the two are somehow mutually exclusive. Before I knew it, my well-trained, instinctive response churned itself out, “Well, my mum’s Australian and…”

This is how my ability to engage socially has been conditioned by a lifetime of pre-empting the quizzical looks, the interrogation on how Māori I really am, the automatic “othering” that occurs the moment I introduce myself. I am programmed to explain myself, to contextualise my appearance so it makes sense to other people, to whom a white face with a brown name does not compute. As a human being biologically wired to seek acceptance by others, I often unconsciously just compromise my own sense of identity for their benefit. And I’m not even innocent of this ignorance myself; my own instinctive defence of my whiteness – that “my mum’s Australian” – is a glaring oversight of Australia’s own indigenous peoples.

And that’s the irony; this “othering” isn’t only committed by Pākehā. I remember, at 6 years old, being pushed by a Māori girl for being a Pākehā who had stolen her land. When I defiantly told her I was from Ngāti Raukawa, she refused to believe me based on how white I was. At 8 years old a Māori relief teacher read my name from the roll, looked over her glasses at me and said, “You’re not Māori, are you?” Again, those experiences weren’t just limited to my childhood; I played a game of netball just yesterday and introduced myself to a new Māori teammate who, when I gave him my name, looked me up and down and said, “Not the name I was expecting.”

I could rattle off examples of these micro-aggressions all day, but I think the picture is clear. This is the bizarre space I occupy as an apparent “white Māori”; possessing too brown a name to fit in with Pākehā but too white-skinned to fit in with Māori.

Frustratingly, these attitudes extend to my writing too. When I was first in talks with my publisher, which specialises in Māori literature, about my novel, I was asked if either of the two main characters were Māori and, if not, why not? I hadn’t really thought about it; I had described one of them as having fair hair and skin only because I vainly wanted him to look like me. Just because I hadn’t explicitly jammed in somewhere that he was Māori didn’t mean he wasn’t. It just meant his appearance wasn’t an indicator of him being Māori or not.

As a Māori writer, this expectation – that my writing should “look” Māori – has been incredibly challenging to break through. People are surprised when they find my novel doesn’t reflect their view of what “Māori literature” is; I’ve had friends tell me they assumed my novel was written entirely in Māori for no other reason than I am Māori. Basically, my novel is about teenagers with superpowers, inspired by comic books, superhero movies, and Harry Potter – it’s about as nerdy and un-Māori in “look” a book could get. But it’s what I enjoy. That’s why I wrote it.

This just doesn’t add up in a lot of people’s heads. They can’t fathom a Māori writer producing a YA sci-fi novel, instead expecting something about Māori gods or taniwhā. It undermines all the aspects of my identity as Māori that shaped the book and therefore absolutely make it – like everything I write – a piece of Māori literature; my novel explores fundamental Māori concepts like life-force and spirit, the complex relationship between older and younger siblings, among others. They’re just not explicitly labelled as such. And they shouldn’t have to be; just like I shouldn’t have to reconcile my identity as Māori with my white skin so it makes sense to others, I shouldn’t have to tokenise my writing with as many Māori references as possible for it to be accepted as Māori literature. In line with that Māori worldview, my book is the result of everything that influenced it, all my experiences that moulded the words I put on the page. If those were the experiences of a Māori person, then the literature is unequivocally Māori too.

Of course, not all Pākehā and Māori have these views. I have been fortunate throughout my life to be surrounded by Pākehā and Māori who simply accept me for who I am, and who protect me when I get tired of sticking up for myself. I must also acknowledge that my skin colour often affords me privilege that others do not have. I do not get stopped by police while driving or walking through the streets. I receive smiles from strangers, am asked for directions or assistance, when my brown friends and family are avoided. I’ve also never been killed or blamed for terrorism based on my skin colour. Who knows how many other scenarios I have been advantaged in due solely to my white skin – probably more than I’ll ever know. And that’s not even beginning to scratch the surface of my privilege as a white man; even if I was brown I still wouldn’t face as much prejudice in New Zealand as a brown Māori woman does. I acknowledge that. This is just an account of my experiences as a Māori with white skin, in a colonised society built upon the distinction of skin colour. It’s one I’m not sure has been explored in literature often.

So I decided to write about it because it’s a theme I touch on in my story “Children of the Mist.” There’s a passage that describes the narrator’s experience having to justify his white appearance to other Māori. At first read it probably seems quite out of place; a monologue that delves much deeper into the narrator’s psyche than any other passage in the story. Mechanically, it serves an important function in the story’s overall conclusion, but it’s also an example of a specific story element inspired by my lived experience. I thought it would be interesting to delve into, because in reading my story – and any other, for that matter – you are not just reading a text that exists independent of anything else. You are reading a text inspired by history, by opinion, by experience. You are reading the sum of everything that came before.

Nō reira, tēnā koutou katoa.